Source Feed: Walrus

Author: Bojan Fürst

Publication Date: June 19, 2025 - 06:30

Climate Change Is Happening. Why Don’t We See It?

June 19, 2025

.text-block-underneath {

text-align: center;

}

.main_housing p > a {

text-decoration: underline !important;

}

.th-hero-container.hm-post-style-6 {

display: none !important;

}

.text-block-underneath {

color: #333;

text-align: center;

left: 0;

right: 0;

max-width: 874.75px;

display: block;

margin: 0 auto;

}

.text-block-underneath h4{

font-family: "GT Sectra";

font-size: 3rem;

line-height: 3.5rem;

}

.text-block-underneath h2{

font-size: 0.88rem;

font-weight: 900;

font-family: "Source Sans Pro";

}

.text-block-underneath p {

text-transform: uppercase;

}

.text-block-underneath h3{

font-family: "Source Sans Pro"!important;

font-size: 1.1875rem;

font-weight: 100!important;

}

.flourish-embed {

width: 100%;

max-width: 1292.16ppx;

}

.th-content-centered .hm-header-content,

#primary.content-area {

width: auto;

}

.entry-content p,

ul.related,

.widget_sexy_author_bio_widget,

.widget_text.widget_custom_html.widget-shortcode.area-arbitrary {

margin-left: auto;

margin-right: auto;

}

.hitmag-full-width.th-no-sidebar #custom_html-45.widget {

margin: auto;

}

@media only screen and (max-width: 768px) {

.img-two-across-column{

flex-direction: column;

}

.img-two-across-imgs{

width: auto !important;

max-width: 100%!important;

padding:0px!important;

}

.main_housing,

.text-block-underneath {

margin-left: 25px !important;

margin-right: 25px !important;

}

.text-block-underneath h4{

font-family: "GT Sectra";

font-size: 35.2px;

line-height: 38.7167px;

}

}

@media only screen and (min-width: 2100px) {

.main_housing,

.text-block-underneath {

margin-left: 32% !important;

margin-right: 32% !important;

}

}

@media only screen and (max-width: 1200px) {

.main_housing,

.text-block-underneath {

/*

margin-left: 25px !important;

margin-right: 25px !important;

*/

}

}

@media only screen and (max-width: 675px) {

.main_housing,

.text-block-underneath {

margin-left: 10% !important;

margin-right: 10% !important;

}

}

.hero-tall {display: none;}

.hero-wide { display: block; }

@media (max-width:700px) {

.hero-wide { display: none; }

.hero-tall { display: block; }

}

ENVIRONMENT

Climate Change Is Happening. Why Don’t We See It?

The photographers making us look at ecological destruction in new ways

BY BOJAN FÜRST

Published 6:30, June 19, 2025

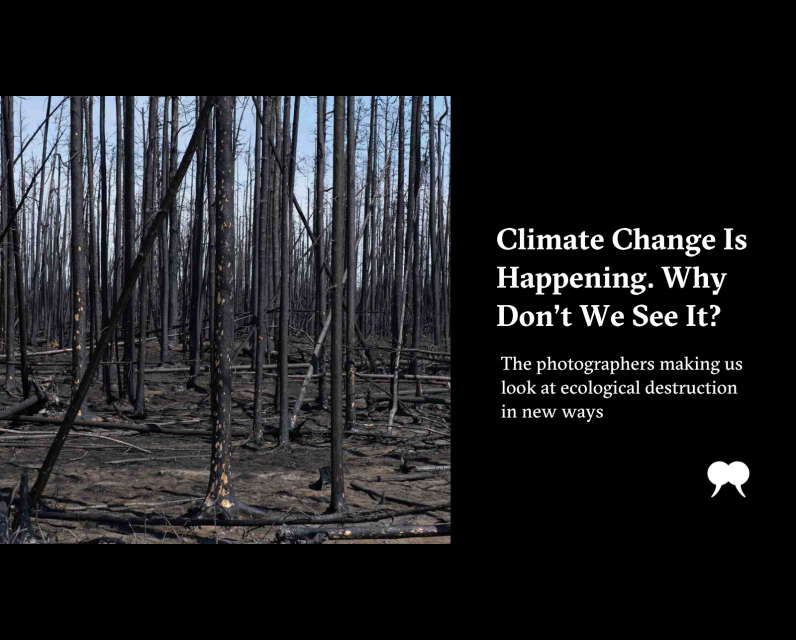

The aftermath of a forest fire in the Northwest Territories (Pat Kane)

In a paper published in 2011, scholars Darryn DiFrancesco and Nathan Young selected six months of news coverage from the Globe and Mail and the National Post in 2008 and went through it with a fine-tooth comb. What they were looking for were news and opinion articles about climate change. They were specifically interested in those that were accompanied by photographs or other forms of visual material. During that six-month period, they found almost 400 stories. “Most of the coverage of climate change had pictures of politicians because they were the ones who were making decisions,” says Young, who today teaches sociology at the University of Ottawa.

DiFrancesco and Young called those images emotionally benign. “There wasn’t any real connection between images and actions, between causes and effects, between consequences and the human impacts,” says Young. “They were comfortable. They weren’t disruptive. They weren’t causing people to sit up.”

But something may be shifting. Last fall, The New York Times Magazine published a visual feature called “Growing Up in Climate Chaos.” This collection of photographs and short interviews from around the world was remarkable for its candour and breadth of experiences. The teenagers in the photographs are growing up in a world that is, in many ways, stacked against them. The portraits caused a range of emotional reactions in the comments: from empathy to every stage of grief, from denial and anger to acceptance. The story was exceptional because of the quality of its reportage, but also because it personalized climate change in ways that we have not often seen in news coverage before.

Photographers, editors, and curators are searching for a new visual language and experimenting with new ways to tell stories amid the global climate emergency. They’re focusing on photography’s ability to evoke emotions, empathy, and human connection at a glance. “People are bombarded with images all the time, and getting any message out is a huge challenge,” says Jonas Harvard, a professor of media and communication science at Mid Sweden University.

Together with his co-author Mats Hyvönen, he interviewed professional photographers to help understand how those covering climate change respond to these challenges. “Scholars talk about the attention economy,” he says. “It’s really, really competitive. And then you have this big and important topic of climate change that people really should be instinctively engaged with.”

The news photographs of the immediate devastation after fires, floods, hurricanes, and droughts are important, but Harvard says we will need to be more sophisticated if we want to communicate the scale and the impact of climate change. He says that the photographers he interviewed are aware of this and are experimenting with different approaches. Some include collaborations with academic researchers. Others negotiate the fine line between aesthetically pleasing images that don’t upset audiences or advertisers and the severity of the impacts they need to depict.

Young points out that there are discrepancies between the metaphors we use, such as “greenhouse effect,” and the severity of the problem. “The metaphor of the greenhouse has been spectacularly counterproductive, because it has this connotation of a gentle warmth that allows things to grow quicker and is a nice place to visit. It has a tropical kind of vibe,” he says.

In the meantime, photographers working on the ground are witnessing ever more horrific impacts of climate change. From rising sea levels to coral bleaching, from devastating wildfires to typhoons to hurricanes and storms increasing in ferocity, all of this is exacting a higher price in human lives and material damages.

D aniel Schwartz, a Swiss documentary photographer and contributor to the VII Foundation, is wary of showing environmental degradation as something beautiful. “I can’t accept this toxicity transformed into something aesthetic,” he says. He feels that in many ways, it simply provides a cover for museums and corporations eager to demonstrate their environmental responsibility. “You put it on the wall, and you’re done with it. You have your fig leaf.”

Delta focuses on South and Southeast Asia. (2025 Daniel Schwartz/VII, ProLitteris, Zürich)

Rising sea levels threaten these regions. (2025 Daniel Schwartz/VII, ProLitteris, Zürich)

His approaches ranged from strict reportage in his work on Southeast Asian river deltas to close collaboration with scientists in his work on glaciers. Delta is a remarkable book. Published in 1997, it features black-and-white photographs from Bangladesh, Burma (Myanmar today), Vietnam, and Cambodia, with a focus on the everyday lives of individuals and their daily struggles with rising sea levels. Possibly the most dramatic photographs come from Sandwip Island, once considered some of the most fertile lands in the world. Today, Sandwip, off the southeastern coast of Bangladesh, is constantly made and remade by coastal flooding, forcing residents to abandon their homes and fields. Each image in the book is accompanied by extensive captions and text providing context. It remains one of the best models of how to blend together photographs and words to create a complex environmental story.

It took almost seven years for him to complete his next work, a book inspired by disappearing glaciers in his native Switzerland. While the Fires Burn: A Glacier Odyssey is a very different book from Delta.

Published in 2017, it features striking, almost abstract photographs from four continents. Many of the photographs were taken from the air, offering Schwartz a unique perspective and allowing him to photograph places such as the Rwenzori Mountains straddling the border between the Democratic Republic of the Congo and Uganda in ways never before seen. Often, the photos appear as diptychs or triptychs; the glaciers and ice appear as a series of curves and tones, monumental and eternal. Except that they are not. From his native Switzerland to Pakistan to Uganda and Peru, Schwartz covered the disappearance of glaciers and invited people to think of these rivers of ice as sites of memory as well as the source of water for millions of people. “We are chroniclers of loss,” says Schwartz.

Canadian photographer Pat Kane has come to the same conclusion as Schwartz—that climate change is personal. In August 2023, as he and his family were evacuating from the wildfires around his hometown of Yellowknife in the Northwest Territories, Kane noticed that many images that were being published in the media missed the bigger story. “In my experience and the experience of the people around me, it was less about the smoke and the flames and more about the actual process of evacuating an entire city, which, to me, was the obvious story,” says Kane, who is also a regular contributor to The Walrus.

A black bear flees smoke near the community of Enterprise in the Northwest Territories. (Pat Kane)

Workers offer free gasoline to wildfire evacuees in Steen River, Alberta. (Pat Kane)

Months later, he tracked down some of the evacuees and created a series of portraits and photographs of small items that were significant to each person during the evacuation. And he wrote a story about every person he photographed, published in The Walrus in August 2024.

This approach allowed him to uncover two uncomfortable and connected storylines: how insufficient the emergency plans in place actually were, and that the evacuation was very much tailored to the privileged.

“I think it allowed all of us to pause and ask: ‘What group would I be in?’ And suddenly you realize how unprepared we are for any kind of these large-scale emergencies,” Kane says. “And I think, among people who live here, it was shocking to see just how much was not planned for, how people fell through the cracks.” He thinks that these kinds of stories also demonstrate the value that local journalists bring to climate change coverage. “It’s really about what is actually happening to our friends and neighbours, our community. And I think a lot of times, magazines, newspapers, and publications forget that that is an advantage,” he says.

Kane is experimenting with new ways of presenting his work. While he continues to publish in magazines and newspapers, including The Walrus and National Geographic, he is also seeking out galleries and small, informal, and intimate spaces where he can present his work to a live audience. It’s another way of building a connection. “I like giving presentations. Every once in a while, I will do one here in Yellowknife just to show people a story that I’ve worked on. It’s kind of like people used to do those slideshows at their home,” says Kane.

On the other side of the world, Lisa Hogben has been observing and covering environmental issues in Australia for a long time, but the past ten years have been the hardest. “Watching the changes in the climate and watching things die, that’s the horrible thing.”

View this post on Instagram A post shared by Lisa Hogben (@lisahogben)Hogben grew up in the suburbs around Sydney and today lives in the Snowy Mountains. The bushfires of 2003 devastated the region, and the increased frequency and ferocity of the fires mean that the ecosystem has no time to recover. “I’m grieving for this childhood that I had that was filled with native animals and bush and beautiful bush walks,” says Hogben. Communicating that grief visually is at the heart of her ongoing project, “Burnt.” The photographs feature the blackened remains of a wild horse and a nineteenth-century miner’s cottage, with only its lone chimney left standing. Hogben is rethinking how we visually talk about climate grief. “Is anyone noticing it anymore?” she says. “Do we have to make things a bit more like a circus so that people go in and get entertained and then get scared by the horror bits? That might be the only way to get it past people.” Hogben, Schwartz, and Kane are grounding their coverage of climate change in deeply personal photography as well. For Kane, making sense of the world for himself and his neighbours is a way to build connections. Schwartz sees his books as a record of the forces we’ve unleashed that are changing the planet. As the severity and frequency of climate change–amplified events increase, the way we communicate about them will need to become ever more sophisticated. What that means in practice is employing a variety of approaches, from highly aestheticized photographs to more personal approaches to classic reportage. However, photographers will not be able to do that alone. Editors, art directors, and curators will need to step up to their responsibilities to commission and seek out work that harnesses photography’s power to evoke emotion and empathy, helping us understand the urgency and existential nature of the crisis we find ourselves in. The post Climate Change Is Happening. Why Don’t We See It? first appeared on The Walrus.

The majority of those Canadians who currently rent have their eyes set on purchasing a home within the next five years, according to Royal Lepage.

June 19, 2025 - 12:01 | Ari Rabinovitch | Global News - Canada

Those Canadians will have to reach a neighbouring country first, however, as airspace over the warring countries is closed, Foreign Minister Anita Anand said.

June 19, 2025 - 12:01 | Sean Boynton | Global News - Canada

About two dozen residents of the Airport Inn inn just outside Fredericton have been told to move out as soon as possible, leaving the longtime tenants worried and upset.

June 19, 2025 - 11:50 | Anna Mandin | Global News - Canada

Comments

Be the first to comment