Source Feed: National Post

Author: Donna Kennedy-Glans

Publication Date: July 13, 2025 - 09:00

'It feels like there's no hope': Many homeless don't want a home. What now?

July 13, 2025

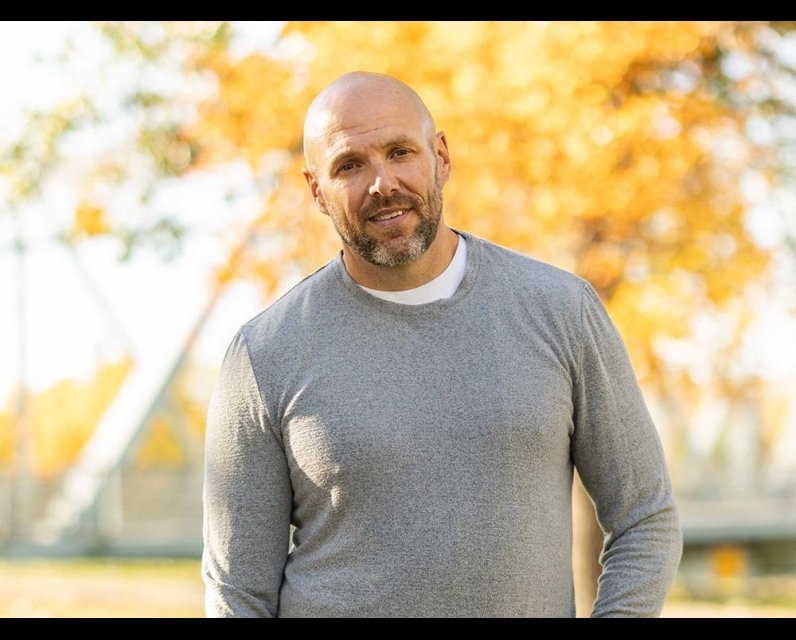

Brent Secondiuk served as a front-line cop in the southern Alberta city of Medicine Hat for 25 years, and understands the futility of dismantling homeless encampments and otherwise dislodging itinerants who decide to bunk down in public spaces.

“We used to call it leaf-blowing … you just scatter the leaves, and the leaves end up somewhere else,” he says.

The most frustrating part, though: Medicine Hat has housing available for the homeless.

“You can be home if you want to,” he laments. “You just choose not to when it’s nice outside,” he says of itinerants who prefer to live rough.

“Years ago,” Brent explains, “we had little to no homeless people, because we had housing available. And I know we still do today. If anybody downtown wanted to get housed, they would be, in 24-48 hours.”

In 2015, Medicine Hat proudly pronounced itself the first city in Canada to “functionally end” chronic homelessness. The city’s housing-first approach — making permanent, stable housing available to the homeless, without pre-conditions — earned Medicine Hat the gold star in the battle against homelessness.

“I think announcing we had zero homeless brought more people here,” Brent acknowledges with a chuckle. Transients would come in from other jurisdictions, assuming Medicine Hat must have all sorts of available housing programs. “The problem,” Brent continues, “is a lot of them, especially in the summer when it’s nice outside and you can sleep rough outdoors,” turn down the housing because it comes with rules.

“And it became trendy to live outdoors and live rough,” Brent explains, “and it just started and snowballed … if person A is doing it, why can’t person B? So it just compounded and got us to where we are now.”

Brent doesn’t know the exact numbers but estimates there are probably 30 to 40 itinerant people living in the two big parks in Medicine Hat’s river valley. While he suspects not all are technically homeless — a few will be tied to that social network, but go back to their residences at night — the numbers are still higher than they’ve ever been, Brent says, “and it looks bad.”

To respond to an uptick in the number of homeless encampments in Medicine Hat, local police launched a “peace team” a few years back. Brent’s optimistic view? That focused approach helped, but there are still people who don’t want to live in a home or emergency shelter.

And for front-line officers — cleaning up garbage and human waste and needles in tents, and continuously checking for fire risk in a hot, dry place like Medicine Hat where a single spark could set off a fire in the entire river valley — it felt like a losing battle, Brent admits.

To address the burgeoning numbers of homeless people, the city cops also boosted patrols of the downtown and public parks where itinerants gather. That strategy helped, but it was also frustrating; the force lacked the practical ability to enforce city bylaws.

Charging the homeless under a bylaw is rather pointless: “It’s a ticket and most of these people don’t have a lot of income and they just don’t pay their fine. Bylaw tickets used to be able to go to warrants, so you could get arrested after a period of time. But that’s no longer the case,” he says.

And with prosecutors no longer prosecuting for simple possession of drugs, he adds, police “still can technically arrest and take the drugs and dispose of them,” Brent says, “but without a charge, it’s (just) a lot of paperwork.”

There is a little drug trafficking within the homeless community, he says, “we’re talking grams or half grams … which is so difficult for drug enforcement units when they’re dealing with big files — kilograms of cocaine — to focus on the little street level thing. But I know all police agencies do it. Every couple of years, they’ll do a street level roundup and charge people. But again, what’s the gain there? It’s more public perception.”

“It’s a lot of work,” Brent says with a sigh, “and the end result is you just have to move somebody along, to do it all over again.”

Hence, the leaf-blowing analogy.

The police service tried to pick its more empathetic officers for the downtown units, more suitable for the work there. “But that wears on you after a while, because you’re constantly dealing with the same small group of people, you know them by name, you’re dealing with them over and over and over and it feels like there’s no hope. I mean once in a while you’ll get a success story, but it’s quite challenging.”

A psychology major before entering the police service at the age of 23, Brent hasn’t become numb to the needs of the homeless; but he did retire from the service, last spring, and launched a second career selling real estate.

Brent’s also empathetic to the public’s fears and concerns. And he knows what happens when homeowners and businesspeople lose patience with rising theft and vandalism; when families avoid the downtown, parks and public infrastructure seemingly overtaken by a transient population. The police get blamed for not fixing the problem.

My take-away from this conversation with Brent: There’s no panacea, no quick fix. Even offering up free or nearly-free housing isn’t luring some itinerants off the streets. Some jurisdictions are now trying the opposite approach, with new legislation to shore up the power of police and courts to tear down illegal encampments, deter illegal drug use and trespassing.

Most notably, in early June, Ontario’s PC government moved forward on its promised Safe Municipalities Act, equipping municipalities with new tools to crack down on the reported 1,400 encampments across urban, rural and northern communities. The new law beefs up trespassing laws and allows police to confront, arrest and fine anyone they suspect of using drugs in public, with fines of up to $10,000 and potential jail time. At the same time, new money is being dedicated to build more affordable housing, shelters and recovery treatment hubs.

“I think some people need forced treatment,” Brent says. “I think when they shut some institutions down, like some of the bigger mental health facilities in the province years ago, that displaced people with mental health issues into communities.”

His empathy is not naive; it’s clear-eyed and more interested in solutions than ideology. He’s learned lessons useful to every city in Canada.

“I know stories of trauma where (homeless) people have been victims of horrific offences, and you feel for them and you want to get them help and put them in a safe place, and that’s what we’re trying to do. But others are just people that take advantage … you know, low-level traffickers, and they’re taking advantage of others.”

National Post

Our website is the place for the latest breaking news, exclusive scoops, longreads and provocative commentary. Please bookmark nationalpost.com and sign up for our daily newsletter, Posted, here.

Ford is recalling nearly a million cars in Canada and the U.S. because the low-pressure fuel pump inside the vehicles may fail — and potentially cause an engine stall while driving, increasing crash risks.

July 13, 2025 - 16:32 | | CBC News - Canada

A young boater is facing several charges after a fatal incident on Weslemkoon Lake in the Township of Addington Highlands on Saturday. Read More

July 13, 2025 - 16:09 | Doug Menary | Ottawa Citizen

Born out of a time when it was almost impossible to reach out and touch someone, an Edmonton art installation appears to be calling out to those on the global stage.“Play it by Ear,” an interactive art installation by Calgary artists Caitlind Brown and Wayne Garrett, has been nominated as one of the top 100 public art projects by CODAworx, a public art industry group.

July 13, 2025 - 15:57 | Aaron Sousa | The Globe and Mail

Comments

Be the first to comment