If You Think We Have Press Freedom, Try Sharing This Story on Instagram

W hen I moved to Canada in 2024, I was shocked to discover that I couldn’t access news pages on Facebook and Instagram. As an Egyptian journalist used to government censorship and blocked websites, I relied heavily on social media for timely news. I still visit a list of news websites daily, but the Meta-owned platforms are crucial for accessing exclusive visual content—like photo series, short videos, and multimedia reports.

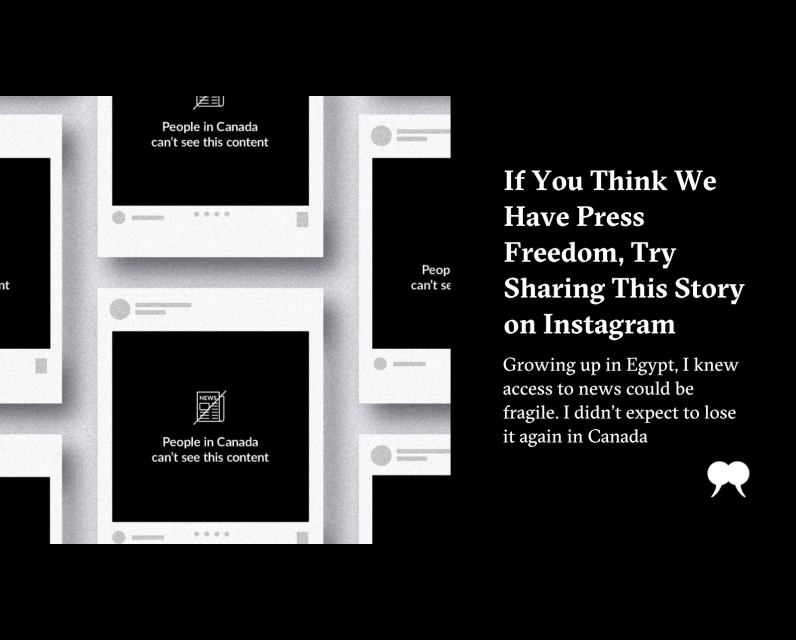

At first, Middle Eastern friends and colleagues would send me urgent news via Instagram or Facebook messages. I’d have to reply, apologizing that their posts were blocked on my end, replaced by the disclaimer that “People in Canada can’t see this content.”

My friends were shocked. Though they were living in countries notorious for stifling dissent, they still had better access to information than I did in Canada. Over time, they stopped sending me news, and I gradually lost my connection to real-time updates from key sources. I no longer see local news from the few remaining independent media outlets I used to follow in Egypt—no updates on the political situation, as Egyptians have been living under police-state rule since a military coup in July 2013, nor on the country’s economic crisis, the arrests or release of high-profile political prisoners who are detained—and abused—on fabricated charges, or even coverage of regional developments like the war in Gaza or military escalation between Israel and Iran.

In June 2023, the Canadian government passed the Online News Act (Bill C-18), which mandates that big tech companies pay media organizations fees to distribute their content. So far, the legislation applies to Google and Meta. While the law aims to ensure fairness in the digital news market and support its sustainability, it has posed serious challenges to press freedom and information accessibility. Google agreed to keep news stories in its search results in exchange for paying $100 million annually to Canadian news organizations. Meta, however, refused to pay up. On June 1, 2023, it began the process of ending news availability in Canada.

The resulting damage is widespread. The Reuters Institute’s 2025 Digital News Report notes that 44 percent of Canadians rely on social media for news. This is especially true for younger people: a 2023 survey by Kaiser & Partners found that 66 percent of millennials and 85 percent of Gen Z prefer to get their news from social media rather than traditional outlets, and about a quarter of Canadians believe that the law and Meta’s response weakened their trust in media.

The declining trust has global reverberations; Canada recently dropped to twenty-first place out of 180 in the Reporters Without Borders (RSF) World Press Freedom Index, down from fourteenth the previous year. Meta’s news ban is partly to blame.

“There’s definitely a connection,” says Clayton Weimers, executive director of RSF USA. “I wouldn’t go so far as to say it’s because of the Meta ban. There’s a lot of factors that go into how we calculate the scores for every country.” But when a large portion of the population gets most of its news and information from a major social media site and that site removes journalism from its platform, “it has to have a negative impact on press freedom.”

From my experience in Egypt, which is ranked 170 in press freedom, social media sites are often places to get around news bans. Back in May 2017, Egyptian authorities launched a wave of internet censorship. The Association for Freedom of Thought and Expression documented 496 blocked websites between May 24, 2017, and February 1, 2018, many of them belonging to news or human rights outlets. These websites turned to social media to reach audiences and encourage them to use VPN tools to access the blocked websites. Despite declining website traffic, many outlets maintained their reach through engaging visual and multimedia content. Social media became a lifeline for information dissemination.

It did for me too. I’ve spent years building an online audience interested in human rights issues and Middle East affairs, and I’m now unable to share my articles with tens of thousands of loyal readers and followers who trust my work. That digital relationship has abruptly ended. At times, when a follower shares one of my stories and tags me, I can’t tell which story they’re referring to. It makes it harder for me to get a sense of what impact my reporting has. What’s worse is the growing sense of isolation. Friends post and comment on news stories, but I can’t see them. I’ve become disconnected from Middle Eastern issues and the conversations shaping public opinion. I imagine this is the reality for millions of immigrants in Canada who rely on social media to stay informed about what’s happening back home.

“It’s sometimes easy to think that as long as journalists are technically safe and not being physically harmed, then they’re fine,” says Katherine Jacobsen, the US, Canada, and Caribbean program coordinator at the Committee to Protect Journalists. “But if no one’s able to read their work and they’re not able to speak with their community, what is the point of all of this if no one can actually access the information that’s being put out there?”

Press freedom isn’t measured solely by whether journalists can do their work, says Weimers. “It’s also about access to information and whether or not citizens are able to consume [news] from a plurality of sources and different voices. . . . It’s a vital function of democracy.” He adds: “It also speaks to an overall climate and a mood toward journalism that the big tech companies, that increasingly govern everything about our society and are the gatekeepers of information, are so hostile to journalism.”

In 2021, Australia passed the News Media and Digital Platforms Mandatory Bargaining Code, a code of conduct that governs commercial relationships between Australian news businesses and certain “designated” digital platforms. Meta complied in Australia. So why is it blocking news in Canada?

It’s possible Meta fears that meeting Canada’s demands could encourage other countries to pass similar laws, forcing the company to pay news publishers globally. Last year, Meta even said it wouldn’t renew its Australian payment deals. Its news ban in Canada, and its renewed standoff with Australian lawmakers, may be a calculated delay to avoid global obligations.

California proposed a similar bill in 2023, requiring platforms to pay for news content. The bill was killed after Google struck a $250 million (US) deal to support journalism and AI research initiatives. Weimers notes that Meta ran a behind-the-scenes lobbying campaign to prevent the bill from becoming law.

“The entire thing happened behind closed doors and without the input of any journalists,” says Weimers. “It’s been viewed as a bit of a betrayal of the entire premise of the original bill, which was to get the tech giants who have profited from the news media to give a little bit of that revenue back to the news media.”

The Canadian public remains the primary victim of the Meta news blackout. The recent wildfires in Manitoba and Saskatchewan have further underscored the dangers of blocking news content during emergencies. A significant portion of the population relies on Facebook for real-time updates—such as alerts about accidents, wildfires, natural disasters, and evacuation notices—in critical moments.

Though it’s been two years since Bill C-18 came into effect, it’s unacceptable to normalize a situation where Canadians are unable to access or share news on Meta platforms. We technically have freedom of expression, and there are no official site bans or state censorship. But in reality, the government cannot broker a resolution with Meta. What are our alternatives? And are we ready for the long fight ahead with big tech companies?

At the end of June, the Canadian government scrapped the digital services tax, or DST, after talks with US president Donald Trump. Under this tax, major tech companies like Meta, Google, and Amazon would have had to pay a 3 percent tax on revenues from Canadian users. White House press secretary Karoline Leavitt said Prime Minister Mark Carney had “caved” to Trump, while the US ambassador to Canada, Pete Hoekstra, said in an interview with the CBC’s Power and Politics that the DST was a “red line” for the United States.

The Trump era may be defined not only by tariffs and a trade war but also by another war centred around big tech, particularly since most of these companies are American. If Carney’s administration is willing to give up the DST to appease Trump, what does that signal about its willingness to stand up to big tech in the long run?

Under different circumstances, I would have shared this article on Facebook to spark a discussion. Now, I’m not sure how to connect with my readers—I just hope they’ll find me somewhere else.

The post If You Think We Have Press Freedom, Try Sharing This Story on Instagram first appeared on The Walrus.

Comments

Be the first to comment