How this 'tooth-in-eye' surgery restores sight to blind Canadians in groundbreaking B.C. program

Warning: This story contains some graphic images

Three blind Canadians regained their sight this year and three more are in line to recover theirs in the coming months, all of them thanks to their own tooth being attached to their eyeball.

While that may sound macabre to some, the highly specialized ophthalmological procedure initially devised in the 1960s has been nothing short of miraculous for the hundreds of patients who’ve undergone it, many of whom have been blessed with sight for decades afterward.

The osteo-odonto-keratoprosthesis operation (OOKP), often aptly referred to as tooth-in-eye surgery, is being performed at Vancouver’s Mount Saint Joseph Hospital by Dr. Greg Moloney, three other specialized physicians and a team of highly trained staff.

It’s taken a lot of work and considerable fundraising to establish the program in Canada, Moloney told National Post in an interview this week, but the results are more than worth it.

“For us, it’s one of the things that we’re most proud of having done in our careers,” he said. “It’s hugely rewarding.”

Like the science of vision — how our brains and eyes use light to create images — the two surgeries are incredibly complex.

In the first, surgeons extract an upper canine tooth — coincidentally, known as the “eye” tooth due to their shape and general position directly beneath the eye — and shape it into a frame of sorts for a plastic “optic” that acts like a lens to allow light to pass through the damaged cornea.

During the roughly six-hour surgery, they also remove a flap of skin from inside the cheek and use it to cover the eye that will accept the natural prosthesis.

The tooth is then stitched into a pocket of skin beneath the lower eyelid where it stays for up to three months, growing a layer of tissue around it. A tooth is used because it contains dentin produced by the body, meaning it won’t be rejected as a foreign object.

In the second procedure, about four to six hours in length, the tooth and new tissue are removed and stitched over the eye.

Moloney said the surgery isn’t an option for patients with glaucoma or with diseases of the optic nerve or retina. It’s reserved for people with severe corneal damage who have no other option and, due to the cost and its complexity, is often seen as a last resort.

But Moloney said, “If you ask these patients, ‘Would you trade the tooth to see again,’ no one ever hesitates.”

“The chance that the prosthesis is still healthy and in place at 30 years is about 92 per cent and the chance that the patient is still seeing to a very high level is about 55 per cent at 30 years,” Moloney said. “Those are odds that these patients will usually take.”

Two of the first three Canadian patients have already come forward with their stories and praise for the medical professionals who brought light back into their lives.

Gail Lane of Victoria, 75, lost her vision as a result of an autoimmune disorder known as Stevens-Johnson Syndrome brought on by a reaction to anti-seizure medication, according to hospital owner Providence Health Care . She was 64 at the time.

Unlike another patient, an unnamed 29-year-old whom the hospital said could see and read documents the day after his second surgery, Lane’s road to recovery was longer. It was about two months before she saw improvements. Now, with prescription lenses, her vision is gauged at 20/50.

“It’s like a miracle to me,” she remarked in a Providence blog, noting the first thing she was able to see well was her blind partner’s guide dog.

“I could see Piper’s tail wagging and then gradually the rest of his whole body came into view. That was wonderful.”

Brent Chapman, 33, lost his sight at 14 when ibuprofen he took for muscle soreness sparked a severe case of Stevens-Johnson Syndrome.

After a 27-day medically induced coma during which one of his eyes had to be removed, Chapman awoke blind in his remaining eye, according to the Delta Optimist.

He underwent multiple surgeries and corneal transplants over the years, all of which granted him only brief periods of sight.

“Emotionally, I couldn’t deal with this roller coaster ride of having a little bit of good vision for just a month or two, and then going blind again,” the North Vancouver man told the Optimist. “It felt like Groundhog Day… for 20 years.”

National Post has contacted Chapman for comment.

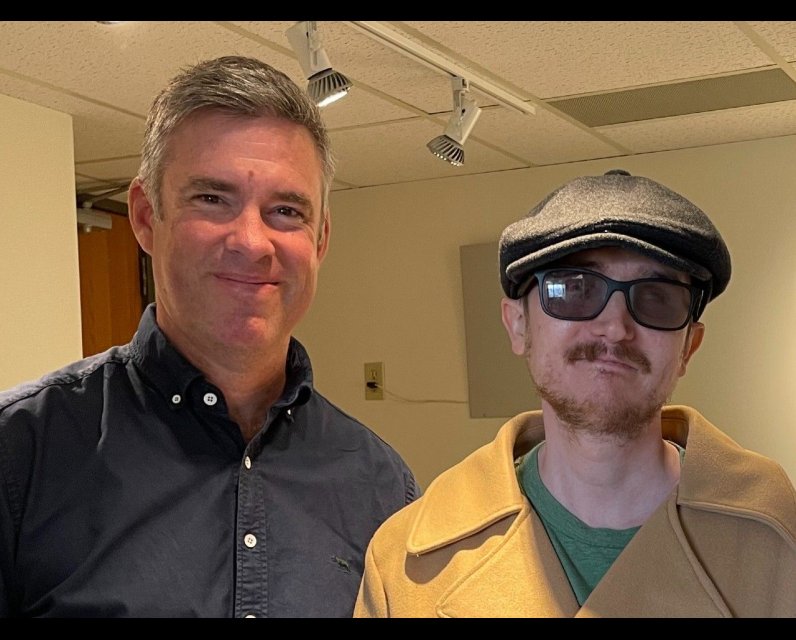

Moloney, an Australian married to a Canadian, has known Chapman since he was a teenager, having treated him during a surgical fellowship in Vancouver around 2009-10.

Given their history and knowing what Chapman and his family have endured over the years, Moloney said he and the team were “all very invested in his outcome in particular.“

“We’ve gone from having very difficult conversations about a fragile situation with his eye to conversations where he just tells me what he’s seeing this week,” Moloney said.

“That’s an enormous relief and satisfaction for us to talk about that.”

It was while working with Chapman that a colleague first suggested Moloney learn OOKP.

When he returned to Australia, where the surgery also wasn’t being done, Moloney approached his med-school friend, Dr. Shannon Webber, a highly trained maxillofacial surgeon, about learning the technique first developed by Italian professor Bernedetto Strampelli in 1963 and since refined.

There are only a handful of places globally where the surgery is performed, and Moloney notes there are only about a dozen doctors with the knowledge.

So, the pair attended a gathering of those surgeons and found a willing tutor in Germany’s Dr. Konrad Hille, who was nearing the end of his career and saw a need to pass on the skills.

After intensive training, they brought the technique back to Australia and established a program that returned sight to eight people before COVID-19 came along and shut things down. By 2021, he was being recruited back to Canada by Providence Health Care, where he quickly set out to establish an OOKP program.

After getting Health Canada’s product approval, Moloney said it took a massive fundraising effort by the St. Paul’s Foundation to get the $430,000 needed for start-up costs, training, equipment and annual operating expenses.

“There was a lot of support from local donors in Vancouver, a lot of support from the local ophthalmology community,” Moloney said. “This was not possible for me to do on my own.”

He credits Webber, who flew from Australia to be part of the surgeries and train staff, and the other surgical team members — maxillofacial surgeon Dr. Ben Kang, retinal specialist Dr. Andrew Kirker, and other hospital staffers. Kang, he noted, plans to help the patients further by replacing their missing teeth.

The next three patients — from Calgary, Ontario and Newfoundland and Labrador, respectively — are due to begin the process in the coming months.

Our website is the place for the latest breaking news, exclusive scoops, longreads and provocative commentary. Please bookmark nationalpost.com and sign up for our daily newsletter, Posted, here.

Comments

Be the first to comment