No One Wants to Buy a Condo

Last month, I moved from Boston to Toronto with my partner. My local friends congratulated me. “It’s a good time for renters in Toronto,” they said. Indeed, rents in Toronto have been decreasing for about a year. Many realtors we spoke with directed us with varying degrees of firmness toward renting a condo. One especially excitable realtor sent us an email that began with the sentence “I’ve put together a BIG list of condo listings which might be great for you!” Since the prices appeared to be at par with those for units in detached homes and apartment buildings, we agreed to take a look.

Most of the one-bedroom condo units we saw were quite small, clocking in at under 700 square feet. A number of them featured bedrooms that were just corners of living rooms walled off by clear panels, such that going to bed each night, I imagine, would feel like being a lizard in a glass enclosure at the zoo. In one condo we looked at, the “den” was a small alcove in the wall that was perhaps no deeper than a foot. I saw an endless parade of one-wall kitchens and “Juliet balconies,” which were not really balconies but windows with railings outside.

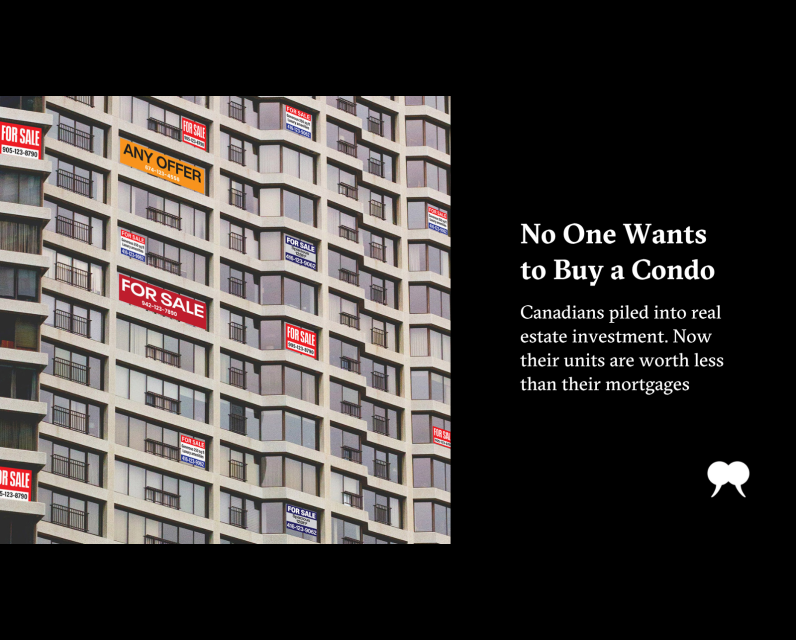

It didn’t take long to figure out why there were so many empty units on the market: it turns out nobody wants to rent a condo, and nobody wants to buy one either. Condo rents have dropped over the past two years, and according to a recent report from the Canada Mortgage and Housing Corporation, or CMHC, condo sales have fallen by 75 percent in the Greater Toronto Area and 37 percent in the Vancouver area since 2022. The market has become so dire that buyers of pre-construction condos are having difficulty closing their purchases. Banks lend money depending on the present value of the property, and some condos are worth less now than they were when the buyers made their first deposit. As a result, developers have been cancelling construction projects. Some experts say we should have seen this coming.

Growing up, I often heard about my parents’ one big regret: not buying property when they got married forty years ago. My parents invested my mother’s dowry in a company that went bankrupt. In contrast, my mother’s sister used her dowry to buy a house in Taichung. My aunt and uncle run a little hardware store, which has done decently if never spectacularly. But the fact that the value of their house has increased exponentially over the past few decades means that they are now actually quite wealthy in assets. The moral of the story is that as soon as I figured out where I wanted to live, I’d better buy some property.

This has always been the conventional wisdom: it’s never a bad idea to buy property if you are able. So what changed?

The simple answer is that many condos built between the late 2010s and early 2020s were constructed not for living but for investment. Since 2000, there has been a steady increase in the proportion of condos used as investment properties. To my surprise, most of the investors were not faceless corporations or foreign investors. Research done by Statistics Canada shows that the typical condo owner is a middle-aged, middle-class Canadian couple. The reigning logic for the middle class was that buying a condo, renting it out to pay for the mortgage, and eventually selling the unit was a solid way to make money. This was especially true in the late 2010s, a period of low interest rates and weak rent control policies. Steady demand for housing, partially caused by increasing immigration, made real estate seem like a sure bet.

Developers knew that most pre-construction buyers were investors rather than people looking to live in the apartments themselves. As a result, they focused on quantity over quality. Vishakh Alex, an architectural designer working in Toronto, said that the directive from developers in the late 2010s was to squeeze in as many units as possible. It is telling that between 1971 and 1990, the median condo in the city was approximately 1,000 square feet, but between 2016 and 2020, the number dropped to roughly 650 square feet.

Developers also sought to cut costs where they could. For example, many of the buildings from around that time were constructed with glass, which is terribly energy inefficient but cheaper than materials that provide better insulation, like precast concrete. The cost is punted downstream to the residents, who end up saddled with exorbitant utility fees to cool the units in the summer and heat them in the winter.

These questionable architectural decisions have not escaped the notice of homebuyers. I spoke with one potential buyer, a woman in her late twenties who works in policy and is looking for her first home. She’s holding out for units constructed prior to 2018, because she observed the same things I did about the newer buildings: the odd glass-enclosure bedrooms, the one-wall kitchens, and the bizarre layouts. Another buyer I talked to, a twenty-eight-year-old lawyer, is taking her time browsing condos. It’s the most expensive thing she will buy, she told me, and she wants to make a good choice that does not involve a bedroom without a window or pillars in the centre of the apartment.

The upshot of all this is that mom-and-pop investors have increasingly struggled to find buyers. In addition to the small size and shoddy quality of the condos, sellers have also had to contend with high interest rates over the past two years—which has rendered more consumers cautious. Meanwhile, stagnant wages and the rising cost of living have reached a tipping point, locking potential buyers out of the process and leaving more units on the market. The combination of reduced demand and excess supply has led condo prices to plummet.

The newer condos embody soulless optimization, as if they were designed by people armed with a list of things that millennials like—dishwasher, in-unit laundry, hidden fridge, built-in microwave, central air-conditioning, flashy amenities—and tried to check everything off while spending as little money as possible.

One unit we saw charged $2,250 per month, roughly the average rent for a one-bedroom in Toronto, but it was situated in a building with an indoor swimming pool, a hot tub and cold plunge, a “sky spa,” a private skating rink, a car wash, wine lockers, a “tasting room,” and a “sky lounge” featuring a full bar. Despite these amenities, I felt boxed in by the expectations of what a developer thinks I want—which is not to say that I don’t want all those things, but it is to say that I want to at least be able to live the fantasy that I am an individual who has particular taste and can think for myself.

There is also the psychological cost of condo living to consider. The buildings we saw offered residents the possibility of working out, watching a movie, going ice skating, and getting a drink without ever meeting anyone outside their income bracket. I was reminded of the condo I lived in several years ago in New Haven, a mid-sized city on the East Coast of the United States.

New Haven is a city riven with inequality. Twenty-five percent of New Haveners live below the poverty line, but the city is also home to Yale University, an institution with an endowment of roughly $41 billion (US). My then boyfriend and I chose to live in a condo because it was not much more expensive than a unit in a house, and the process of renting the condo was streamlined for students like us. It was the end of the semester, and we were juggling apartment viewings with wrapping up term papers and final exams, so we bit. But over the two years we lived there, I saw how condo living changed the way I interacted with New Haven. I felt increasingly disconnected from the city, moving between my apartment complex, with its sparkling lobby, security guards, and smiling front desk personnel, and the university, another fortress filled with campus police and doors that required student IDs to swipe open.

Yet, as city populations continue to grow, there’s nowhere to build but up. It hardly bears repeating that there is a housing crisis in Canada. Young middle-class people looking to buy their first homes can rarely afford the kinds of houses that they might have grown up in—a cute triplex on a tree-lined street in Trinity-Bellwoods, Toronto, for example, or a townhouse in Kitsilano, Vancouver, with a view of the ocean. And so it is to the condos we must go.

But it is also true that condo living does not have to be, and perhaps should not be, defined by the biggest developers looking to squeeze every drop of profit from mom-and-pop investors and homebuyers. Laurence Dutil-Ricard, a Toronto-based real estate lawyer, told me that instead of trying to solve the housing crisis with colossal condo buildings, we might be better served by reassessing some of the red tape that currently snarls new projects.

To construct a new building in Toronto, for instance, a developer has to navigate a gruelling terrain of bylaws, certificates, lender requirements, and permits governed by different stakeholders, such as the building department, the planning department, and the committee of adjustments. To add to the headache, Dutil-Ricard said, the rules also keep changing. Streamlining the process would help small- and medium-sized developers enter the market more easily and provide more options for homebuyers.

Alex also noted that developers are shifting from constructing condos for sale to purpose-built rentals, which are buildings with units designed to be rented. Under this model, developers focus less on maximizing the number of units per building, because they now have a stake in whether people would actually want to live in the units.

In the end, we passed on the condo in the building with the sky spa. We rented, instead, a unit perched on top of a bubble-tea shop. The apartment has quirky light fixtures, a raggedy little wooden back patio, and no dishwasher. It isn’t that much cheaper than a condo, but it is spacious. A taqueria across the street blasts music from noon until midnight most days, and we are so close to the street, we can catch snippets of conversation if the windows are open. Buses and trucks rumble by regularly, and every so often, a motorbike roars down the street. The building is old, though, with a sturdy brick facade, so the apartment is quite soundproof if we close the windows.

But I always leave them open.

The post No One Wants to Buy a Condo first appeared on The Walrus.

Comments

Be the first to comment