Source Feed: Walrus

Author: Harrison Browne

Publication Date: May 24, 2025 - 06:30

I Was the First Transgender Player in Professional Hockey. Then I Had to Walk Away

May 24, 2025

.text-block-underneath {

text-align: center;

}

.main_housing p > a {

text-decoration: underline !important;

}

.th-hero-container.hm-post-style-6 {

display: none !important;

}

.text-block-underneath {

color: #333;

text-align: center;

left: 0;

right: 0;

max-width: 874.75px;

display: block;

margin: 0 auto;

}

.text-block-underneath h4{

font-family: "GT Sectra";

font-size: 3rem;

line-height: 3.5rem;

}

.text-block-underneath h2{

font-size: 0.88rem;

font-weight: 900;

font-family: "Source Sans Pro";

}

.text-block-underneath p {

text-transform: uppercase;

}

.text-block-underneath h3{

font-family: "Source Sans Pro"!important;

font-size: 1.1875rem;

font-weight: 100!important;

}

.flourish-embed {

width: 100%;

max-width: 1292.16ppx;

}

.th-content-centered .hm-header-content,

#primary.content-area {

width: auto;

}

.entry-content p,

ul.related,

.widget_sexy_author_bio_widget,

.widget_text.widget_custom_html.widget-shortcode.area-arbitrary {

margin-left: auto;

margin-right: auto;

}

.hitmag-full-width.th-no-sidebar #custom_html-45.widget {

margin: auto;

}

@media only screen and (max-width: 768px) {

.img-two-across-column{

flex-direction: column;

}

.img-two-across-imgs{

width: auto !important;

max-width: 100%!important;

padding:0px!important;

}

.main_housing,

.text-block-underneath {

margin-left: 25px !important;

margin-right: 25px !important;

}

.text-block-underneath h4{

font-family: "GT Sectra";

font-size: 35.2px;

line-height: 38.7167px;

}

}

@media only screen and (min-width: 2100px) {

.main_housing,

.text-block-underneath {

margin-left: 32% !important;

margin-right: 32% !important;

}

}

@media only screen and (max-width: 1200px) {

.main_housing,

.text-block-underneath {

/*

margin-left: 25px !important;

margin-right: 25px !important;

*/

}

}

@media only screen and (max-width: 675px) {

.main_housing,

.text-block-underneath {

margin-left: 10% !important;

margin-right: 10% !important;

}

}

.hero-tall {display: none;}

.hero-wide { display: block; }

@media (max-width:700px) {

.hero-wide { display: none; }

.hero-tall { display: block; }

}

SPORTS

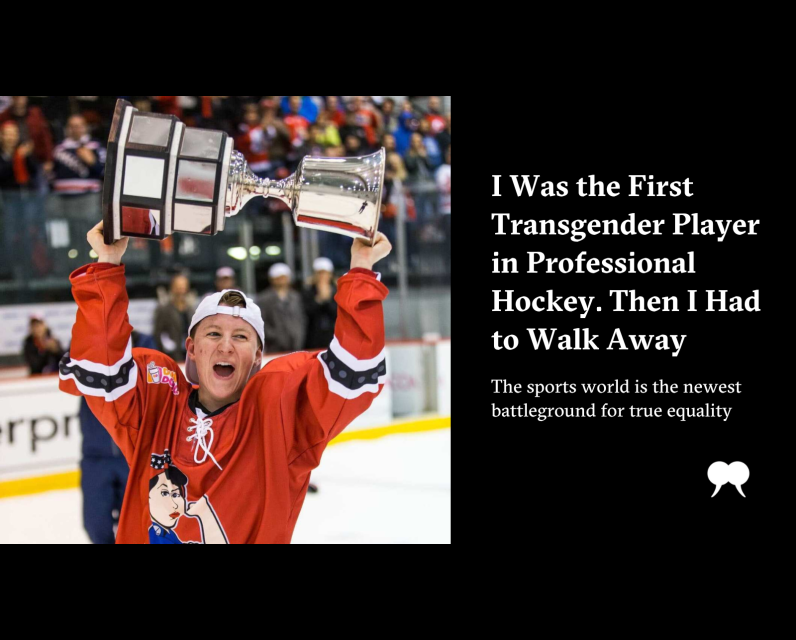

I Was the First Transgender Player in Professional Hockey. Then I Had to Walk Away

The sports world is the newest battleground for true equality

BY HARRISON BROWNE

WITH RACHEL BROWNE

Published 6:30, MAY 24, 2025

Harrison Browne (Photograph by Michael Hetzel)

“You ready?” the doctor asked as he took a seat across from me in his office, syringe poised.

“Yep,” I replied tentatively.

“Okay. One, two, three.” He jabbed my outer right thigh an inch and a half deep into my muscles. It all felt so sudden.

Even though I’d spent a long time mentally preparing for this, I’d never had a shot in my leg before. Almost immediately, it felt achy. Then my ears started ringing. It was a vivid point of no return. I watched as the doctor pushed the thick liquid into my body. As soon as that first drop of testosterone hit my bloodstream, I said goodbye to my life as a professional hockey player and my identity as an elite athlete. It hurt.

As a kid, I always played women’s sports. I really didn’t think too much about how men and women are divided in athletics. I played on the women’s and girls’ side without question. As someone who was born a girl and lived my childhood as one, I didn’t know there were any other options. I was celebrated as a woman athlete, and the more I accomplished, the deeper it became interwoven with my own identity, how people viewed me, and, ultimately, my place in the world.

Hockey was also my happy place, and it was where I learned to push myself and thrive alongside other people in a team environment. It was home. In less than a decade, I had gone from putting on my very first pair of hockey skates (and falling flat on my face) to being selected to represent my country on Team Canada in the 2011 Under-18 Women’s World Championship in Stockholm, Sweden.

To understand the crossroads I was at before I took testosterone in 2018 while I was playing professionally, we must go back to my days as a college athlete. At the time that I entered college, in 2011, professional women’s hockey players were getting paid nothing; they were all essentially volunteers. The pinnacle of achievement in women’s hockey at that time was either playing for the national team and representing your country in international competitions or getting a coveted full-ride scholarship at an American college. I had achieved both and knew I was locked into women’s hockey for at least four years while I completed my college studies. I had worked my entire life for this, so the thought of jeopardizing it to undergo gender-affirming surgery or take hormones wasn’t remotely fathomable.

While I was playing hockey for the University of Maine Black Bears, I wasn’t aware of any trans college athletes or any policy for trans inclusion that existed. But in any case, I wasn’t looking for such answers, as I had decided to remain closeted—to the general public at least. It turns out there was indeed a National Collegiate Athletic Association—NCAA—policy that was in place at the time that had been implemented in 2011, just before I enrolled. That policy, considered “groundbreaking,” was created after a basketball player, named Kye Allums, on the women’s team at George Washington University came out as a trans man, becoming the first trans NCAA Division I athlete. “I decided to do it because I was uncomfortable not being able to be myself,” Allums told reporters.

I didn’t know about Allums’s story until after I had come out, but I wish I knew about it sooner. Maybe I wouldn’t have felt so isolated in my own struggles. Allums and I share so many similarities: he identified as gay in high school and realized he was trans shortly after starting college. We were both stressed about coming out as trans to our family members and friends. He, too, was worried that doing so would jeopardize his college scholarship. He also delayed hormones so that he could continue playing on his team.

The 2011 NCAA policy allowed transgender student athletes to participate as long as their use of hormone therapy remained consistent with the association’s policies and medical standards. The policy also stated that a trans man (assigned female at birth, or AFAB) student athlete who received a medical exception for treatment with testosterone may compete on a men’s team but is no longer eligible to compete on a women’s team without changing the team status to a mixed team. A mixed team—made up of men and women—is eligible only for men’s championships. And a trans woman (assigned male at birth) student athlete who is undergoing testosterone suppression may continue to compete on a men’s team but may not compete on a women’s team without changing the team to a mixed-team status. That requirement remains in place until they have completed one calendar year of documented treatment.

All of this seemed so complicated to me, especially as I was navigating intense hockey schedules and my studies for my business degree at the same time. In the grand scheme of life, four years—just four playing seasons—isn’t a lot of time to make the most of this small window in my sports career. I couldn’t get distracted by anything, not even myself.

College was also a time for me to figure out who I was, free from the watchful gaze of my parents and the microscope of my small, conservative hometown. I was living on my own for the first time and surrounded myself with like-minded people, and I gained confidence to express myself in a more masculine way—it was liberating. My college teammates became my second family, and I soon trusted them with my biggest secret.

In my second year, I came out to my team and coaches as a transgender man and had my first taste of living my life as Harrison within my hockey locker room. I still wasn’t sure that I could compete on the women’s side as a trans man, so beyond coming out to those people, I didn’t come out publicly out of fear that I could lose my scholarship and not be allowed to play anymore. I thus lived a double life for my entire college career—being Harrison in one aspect and someone I wasn’t in every other way.

It was agonizing and disorienting. For trans men and AFAB non-binary elite college athletes, often their only option is to transition socially (when a trans person changes aspects about themselves, separate from medical treatments, to align with their gender identity), as they are beholden to strict policies. Those considering a medical transition with hormones will most likely take testosterone, a banned substance for athletes who play on women’s teams, as it’s seen as providing an unfair competitive advantage.

It was at the end of my sophomore year that I knew I had to do something with regard to my gender dysphoria and my desire to live openly as a trans man. But hormones were absolutely out of the question. I didn’t know that, beyond letting my teammates know my secret, there were other, officially sanctioned, ways for me to be Harrison, a man, in my league.

I n late spring, after our season had ended in a disappointing way, the school’s compliance officer called me into her office. She mentioned that one of my teammates—who remained anonymous—had told her that I was transgender. My anonymous teammate wasn’t being intentionally malicious, as far as I could tell, but I was stunned and a bit confused as to why I had been outed without my consent. The compliance officer, however, was completely nonchalant about me being trans and wanted to support me in my social transition while reminding me about the NCAA’s testosterone policy; I assured her I wasn’t planning on taking the hormone. She also said I could have my own locker room if I wanted and change my name and pronouns on the roster.

I decided not to take her up on either of these options. I wanted to get ready for games and practices alongside my teammates; the locker room is a place of joy and camaraderie. It didn’t feel like a “women’s room” to me—it’s simply where I felt most comfortable. As for publicly changing my name and pronouns, I just wasn’t ready yet. I was too scared of how I might be perceived by those outside my little hockey bubble and how my parents would react, as I still wasn’t out even to them at this point.

Looking back, I realize how important it is for trans and non-binary student athletes to have those options, whether or not they take them. These choices provide a baseline of institutional acceptance and acknowledgment for gender-diverse athletes at all levels, something that is becoming even more important amid the anti-trans backlash that is only getting worse these days. The process of transitioning socially is something that’s often left out of the conversations about trans and non-binary people in general and for athletes specifically. The focus is usually on the physical and medical aspects of transitioning.

At the beginning of my journey in the public eye after I came out publicly, my body was all journalists really focused on. I was asked numerous times about surgeries and other very intimate things—it was jarring and violating. They likely would have never asked cisgender athletes such personal and specific questions. For many trans folks who don’t undergo surgery or take hormones, it can be isolating and leave them feeling like they aren’t valid members of the community.

In recent years, I’ve been having conversations about this with Athlete Ally, a group based in New York that supports LGBTQ+ athletes who compete in sports at all levels, from recreational to elite. Anna Baeth, Athlete Ally’s director of research, told me, “It is exceedingly uncommon that college athletes are going to undergo hormone replacement therapy, any sorts of surgeries, while they’re in school.” And there’s a big void right now in college-level sports both in terms of the policies and overall awareness among coaches and administrators and in terms of supporting athletes who seek to transition at least socially.

Filling this void will make things more comfortable and inclusive for all athletes and help people understand that there’s more than one way to be trans. The only examples of transgender people I was aware of before I came out were folks who had transitioned physically and medically. I didn’t fit into that category yet. I didn’t think I would be accepted as a man in society, let alone in men’s athletics, as someone who didn’t necessarily look or sound like one.

Had I been able to see more out trans people who had only socially transitioned, it would have empowered me to come out sooner and live my truth at an earlier age. But more importantly, it would’ve given me the knowledge that I can absolutely be myself while still playing my sport. I thought it had to be one or the other, but it can and should always be both.

B y the time I was playing Division I hockey for the University of Maine in the NCAA, I was grappling with my gender identity and what being a transgender man meant for my future in the sports world. I was a woman athlete, I was on the women’s college hockey team, and, in every space, from classrooms to parties, that was my identity. I wanted to be seen as just an athlete, without the “woman” in front of it, but that could never be. When I was around my teammates, we did everything together, from eating meals to attending classes, and every time I was surrounded by them, by default I was assumed to be “one of the girls” or “ladies.” Everything from my scholarship to my friendships hung in the balance as I worked through the realization that I actually wasn’t like the rest of my team; I was a man and I was transgender.

I knew hormone therapy—in my case, testosterone—is what I wanted and ultimately needed in order for society to view me as a man. It’s important to note that this is my personal journey and my own unique vision for my future. Not all trans people follow this path or feel the need to “pass” as cisgender to others, and that is completely valid. Not every trans person undergoes a medical transition. But for me, it was vital to be seen and accepted as a man. That meant changing my physicality through testosterone: my voice would drop because my vocal cords would thicken; my Adam’s apple would grow; I’d grow facial and body hair in new places; my face shape, hairline, and muscles would change.

I was warned that hormones would make my skin break out like crazy, but I accepted and even welcomed that, knowing it would be my rite of passage as someone going through testosterone-driven puberty. I was looking forward to the day I could wake up and look in the mirror and see me, the me I’d been suppressing for a decade to stay in women’s hockey. But I had no idea how to even begin accessing hormones.

I had seen some trans men on YouTube who shared their experiences and medical journeys in the US, but I didn’t know any trans people personally. The whole process seemed so intimidating and out of reach. I felt alone and anxious. Transgender health care wasn’t something I learned about in school, talked about with my friends, or even encountered in the media. There were very few online resources available that applied to Ontario, my home province, and I didn’t know how my doctor would react to being asked about testosterone or even to the fact that I was transgender.

I’m from a relatively conservative city and family where issues regarding LGBTQ+ people never really came up, and if they did, they were mostly frowned upon. The only thing that gave me real confidence to proceed with medically transitioning was the support I had from my hockey teammates at college, the Black Bears, to whom I had recently come out as trans.

Women’s hockey, for the most part, is an extremely LGBTQ+ friendly sport globally, much more so than the men’s side. Most of the teams I played on over the years had many lesbian and bisexual women on them. Since women’s hockey is filled with queer people—and, well, women—it’s a sport with individuals who have dealt with being discriminated against based on who they are as a person. As I walked into my locker room one day in my junior year, I was getting mentally prepared for a special team meeting before one of our practices. This was my moment to come out to my entire team as trans for the very first time. To finally be my true self in hockey among my teammates.

I wasn’t nervous. Most of my fellow players were queer, so I knew they would understand me on some level, even though I would be the only openly trans member of the team. Acceptance isn’t a new concept to them. “I’m still the same Brownie,” I said, referring my hockey nickname. “But can you use he/him pronouns for me?” Even though most of my teammates didn’t understand intimately what being transgender was, they could understand other elements of what I went through. Although I wasn’t exactly sure how my teammates would react to now having a man among them, I knew deep down that they would accept and support me.

At the end of the day, we were a team. Their reaction to my coming out was pretty anti-climactic, to be honest, and we just continued getting ready for our practice as always. At the moment we hit the ice, not that much had changed. Sure, some of them poked fun at me later when I started letting my underarm hair grow freely, but I put them in their place!

Being Harrison, a man, in my hockey locker room and on the ice allowed me to really figure out who I was and how I wanted to be perceived. A huge weight had been lifted off my shoulders, and I felt free to express myself in ways that I never had the courage to before, such as cutting my hair short for the first time and wearing men’s clothing and sports bras to flatten my chest—all things that count as socially transitioning. This can include someone changing their name, their pronouns, their hairstyle, clothing, and so on. Although socially transitioning alleviated some of my gender dysphoria and anxiety, I was still keeping part of myself hidden.

By 2018, when I was playing professionally in Buffalo, New York, with the Buffalo Beauts of the National Women’s Hockey League, I didn’t want to hide anymore. I decided to come out publicly as a trans man through an ESPN article that went viral and began an intense cycle of international news coverage. This media firestorm was stressful, but it prompted the hockey world to develop a type of cheat sheet for how to refer to me: my new first name, Harrison, was now on the roster, and there was widespread knowledge that I used he/him pronouns.

The same couldn’t be said of the non-sports world. I always had to stop and correct people who referred to me by my old name or she/her pronouns, many of whom were confused or dismissive. Being constantly misgendered and bound by an assigned-female legal name was what prompted me to retire from women’s hockey sooner than I would have if I wasn’t trans. Shortly after I announced my retirement through the New York Times, I finally mustered up the courage to call my doctor’s office to talk about hormone therapy and explore taking the substance that would officially ban me from women’s hockey and alter the course of my life.

M y family doctor is the same one who delivered me at birth, in 1993, and ceremoniously announced, “It’s a girl!” before handing me over to my parents. So, naturally, when the receptionist asked what the appointment was for, I froze. After a deep breath, I sputtered, “I’m trans and I want to go on testosterone!” To my relief, the receptionist had no reaction and booked me without further question. Luckily, there was a new physician at the office who just happened to specialize in transgender health care and was filling in for my regular doctor, who was on leave.

Most doctors aren’t well versed in transgender health issues, let alone have experience working with actual trans patients. I felt incredibly fortunate to be cared for by someone who understood my specific needs, and that I didn’t have to go on a wild goose chase for hormone therapy.

There were still several hurdles to go through, however. First, I had to speak with the doctor about my medical and gender history and get a formal diagnosis of gender dysphoria, a term that describes the sense of unease a person might have because of a mismatch between their sex assigned at birth and their gender identity. That diagnosis was more of a formality since I’d already been living openly as a man for four years. Next, I had to undergo multiple blood tests to assess my existing hormone levels. I was checking off the boxes quickly. Finally, I got my hormone prescription at the pharmacy and took it back to the doctor, who administered it the first few times until I learned to do the weekly injection myself.

I remember thinking that my life was about to start. I had been envisioning this day from the moment I realized I was trans. At the same time, I was about to lose my identity as an athlete. I sat in the chair in my doctor’s office, heart pounding and knees bouncing, as I watched him ready the injection. He plunged the needle into a small vial to draw up the golden liquid—testosterone.

While it was crucial, and even lifesaving, for me to abandon women’s hockey so I could finally begin to live as my true self, it was still excruciating to have to make that call. This is a reality for far too many transgender and non-binary competitive athletes who often must sacrifice their authentic selves for their sport. In 2018, the year I made the difficult decision to stop playing hockey and pursue hormone therapy for my physical transition, the NWHL did not allow trans men to take testosterone and continue to participate.

Three years later, in September of 2021, the NWHL changed its name to the (gender-neutral) Premier Hockey Federation—PHF—and updated its trans policy so that players like me were no longer prohibited from taking testosterone while they were playing. This was the first trans policy of its kind to not focus on hormones, and the first policy to mention non-binary athletes as well. It was a pivotal moment in professional sports, not to mention a bold move at a time when transgender participation was facing increased hostility and scrutiny. This groundbreaking change came too late for me and my hockey career. If I had been allowed to take testosterone in the years that I was part of that league, I still might be playing the sport I love.

It’s now been over a decade since I came out as trans to my team, more than eight years since I came out publicly, and more than six since I retired from professional women’s hockey and went on testosterone. Although I no longer play in competitive leagues, hockey will always be the love of my life, and I’m dedicated to defending the inclusion of all players in all sports.

Today, gender-diverse people, athletes and non-athletes alike, are facing an unprecedented threat to their very existence. This includes their right to play sports on the team of their choice. And the worsening struggles of trans athletes are occurring while their access to proper health care is being eroded. We can’t talk about these two issues as if they’re separate. They are deeply connected.

It’s never been more important to debunk the misinformation and misunderstanding regarding trans athletes in order to improve our society as a whole and pave a peaceful path for future athletes of all genders and sexual orientations. The sports world has become the newest battleground over the fight for true equality. What happens in sports reflects how tolerant we are as a society.

Why is inclusive participation in sports so important when not everyone is an athlete? It’s important because when we exclude trans people in one area of society, it sets a dangerous precedent to exclude trans people in other areas. We aren’t seen as full members of society unless we have the same exact rights as everyone else, and that includes sports. We’re not seen as human if we don’t have access to the right bathroom. We’re not seen as human if we don’t have access to health care. We’re not seen as human unless we have access to the same places as everyone else. This is about so much more than sports.

Excerpted from Let Us Play: Winning the Battle for Gender Diverse Athletes by Harrison Browne and Rachel Browne. Copyright 2025. Excerpted with permission by Beacon Press.The post I Was the First Transgender Player in Professional Hockey. Then I Had to Walk Away first appeared on The Walrus.

The Canadian Union of Postal Workers said Saturday it was still reviewing the Crown corporation's latest offer and expects mediated talks to resume this weekend.

May 24, 2025 - 15:15 | Sean Boynton | Global News - Canada

Five people, including four teens, are dead after a crash involving two SUVs and a transport truck in Ontario. OPP continue to investigate.

May 24, 2025 - 15:05 | Prisha Dev | Global News - Canada

Five people, including four teens, are dead after a crash involving two SUVs and a transport truck in Ontario. OPP continue to investigate.

May 24, 2025 - 15:05 | Prisha Dev | Global News - Ottawa

Comments

Be the first to comment